What is an EXPLANATORY TRANSLATION, how does it differ from other translations, and why would you want to use it for your Bible reading?

A White Paper, July 2024

Abstract:

We say that we produce an explanatory translation. But what is that? Our goal is to produce a translation from the original Koine Greek manuscripts that is true to the original Koine Greek but is focused more on communicating to a 21st century American audience what the first century Greek speaking audience was experiencing and feeling as they read and thought about the apostles’ writings. How is this different from other popular translations such as the ESV, Amplified, and King James? Most other popular translations employ a translation philosophy of doing basically a word-for-word translation where they use the English word whose meaning is closest to the original Greek word. That sounds like a reasonable approach until you learn that, for many important theological concepts, there often are not any English words that are very close to the original Greek word. But there are also other considerations. This paper seeks to explore the differences in various translation philosophies, and to better understand their comparative strengths and weaknesses.

The New Testament was written in Koine Greek by the apostles Jesus Christ appointed to write it. The Holy Spirit superintended the work so closely that the Bible claims the words written on those original scrolls were actually “breathed out” by God Himself. These original Koine Greek writings, that we now call the New Testament, are literally the words of God written for His Church.

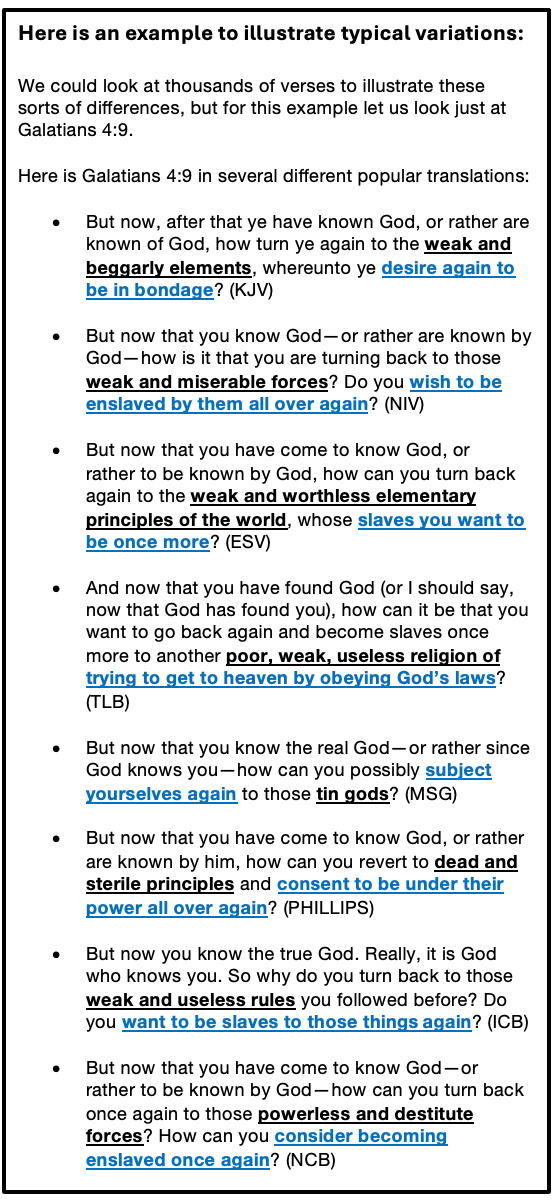

When a Bible translator translates these original Koine Greek Scriptures into English, usually that translator is a competent Koine Greek scholar, and does their best to faithfully translate the Koine Greek into English. So, why are there over 400 publicly available translations of the Bible—all different from each other? Some are so different that an average Bible student may not recognize some of these translations as coming from the same original source text—but they are.

After studying the differences in the example box to the right, well…hopefully, you get the idea. The differences can be significant. How do we account for such variation? The original Koine Greek text is not in question. All these translators are translating the same source Koine Greek text for Galatians 4:9, which is:

ΝΥΝΔΕΓΝΟΤΕΣΘΕΟΝΜΑΛΛΟΝΔΕΓΝΩΣΘΕΝΤΕΖΥΠΟΘΕΟΥΠΩΣΕΠΙΣΤΡΕΦΕΤΕΠΑΛΙΝΕΠΙΤΑΑΣΘΕΝΗΚΑΙΠΤΩΧΑΣΤΟΙΧΕΙΑΟΙΣΠΑΛΙΝΑΝΩΘΕΝΔΟΥΛΕΥΕΙΝΘΕΛΕΤΕ

(NOTE: just a trivial point of clarification for some early Greek students who may be confused by the above string of letters: The above representation is the way the text was originally written by the apostles, but most present day translators work from a modernized rendition which does not change any of the original letters or their word order, but rewrites it in lowercase letters and shows the word boundaries with spaces, and often adds pronunciation marks; so it would appear in this more easily readable form:

νῦν δὲ γνόντες Θεόν μᾶλλον δὲ γνωσθέντες ὑπὸ Θεοῦ πῶς ἐπιστρέφετε πάλιν ἐπὶ τὰ ἀσθενῆ καὶ πτωχὰ στοιχεῖα οἷς πάλιν ἄνωθεν δουλεύειν θέλετε )

The point of the above Galatians 4:9 example is to provide some illustrative evidence of this fact: There is no such thing as an exact translation from one language to another. This is particularly true when the original language is from the far distant past and a very different culture.

The translation of a Koine Greek text from first century Greek/Hebrew culture, to 21st century American English culture(s) is often challenging at best. As we have said, it is not possible (no matter what some may wish) for any modern English translation of a New Testament book to exactly and precisely represent all of the logical, emotional, and social implications of the original Koine Greek text of any New Testament book.

This does not mean that a faithful English translation of the original Greek manuscripts is not useful. If you don’t read Koine Greek, a popularly well-respected translation (such as KJV, ESV, NIV, NAB, NJB, PHILLIPS, MSG, NLT, etc.) is much, much better than nothing, especially if you also read multiple versions and commentaries in an attempt to ferret out the more subtle and often obscure meanings present in the original Koine Greek text. After all, it is the Holy Spirit that interprets and instructs you in the intended meanings of the text, regardless of what language you are reading it in.

But as a Koine Greek scholar and Bible translator, it is clear that the original Koine Greek text is not completely, or even sometimes even accurately, represented in many popular the English translations. That is not because the translator does not understand Koine Greek, or because the translator has inserted his bias according to an explicit agenda, because I am convinced that most translators are well intentioned. The reason for the incompleteness and the misrepresentations is because it is REALLY hard to simultaneously translate all the textual connotations and implications and emotional passion and cultural references of a 2000-year-old document into a modern language.

One example of this is my own experience from when I first started studying Koine Greek in earnest about 35 years ago. I was stunned to see how deep and passionate the emotion of the Apostle Paul was in his writings to the various churches. I was very surprised because that emotional passion was not well represented in any of the English translations I was regularly using (which, at that time, were primarily: NKJV, NIV, NAS, and the Amplified). At first, I felt robbed and a little betrayed at these omissions. But as I got into the task of Bible translation, I began to understand why this was the case. It was not because they wanted to do a bad job of translating; it was because it is NOT POSSIBLE to completely translate the complete meaning of the Koine Greek into English. Not that it is hard, but that it is actually truly impossible. The reasons for this are many and significant.

Furthermore, every translation project adopts a translation philosophy that essentially prioritizes which aspects of the original will have priority in the translation (and which will be neglected). Some aspects that that are considered in determining a translation philosophy are:

- How long should the translation be? Options are:

a. As short as possible without leaving out the most obvious intention of the original meaning (these translations are the most marketable because people want a simple to read and understand short version of the text: For example, would you rather have your children memorize John 3:16 in the ESV (24 words) or in The Amplified translation (45 words) or an explanatory translation such as GCTM which would use more than 60 words?)

b. Understandability of the translated text by the average English reader needs to be as close as possible to the full understanding of the original 1st century reader of the Koine Greek. It needs to include not only the full cognitive content, but also the emotional, cultural, and life application implications of the original text. These more complete translations are MUCH longer than the more marketable shorter translations. Because it is harder to get full funding/payment for the effort (which is significantly greater than the shorter translations) to produce these more complete translations, they are rare.)

An example illustrating how a verse can be translated to more clearly capture the fuller cultural meaning that would have been understood by the 1st century Greek reader, is the difference between the more literal ESV and the explanatory translation of the GCTM for Galatians 4:1-3:

“I mean that the heir, as long as he is a child, is no different from a slave, though he is the owner of everything, but he is under guardians and managers until the date set by his father. In the same way we also, when we were children, were enslaved to the elementary principles of the world.” (Gal 4:1-3, ESV)

Compared to the explanatory translation of those same three verses in the GCTM:

“Consider the example of a child whose wealthy parents die while the child is still young. In their will they leave a significant inheritance for the child, but until the child reaches the age set by the parents, the trust fund is administered by an appointed trustee who has full legal authority to decide how the trust funds will be used to meet the legitimate needs of the child. Until the child reaches the age set in the parents’ will, the child cannot spend any of the money in the trust fund even though technically and legally all that money belongs to the child. In this sense, the child has no more freedom to decide what activities he could indulge than a poor person would. He has to live under the protection and provision and direction of the trustee until the age set forth in the parents’ will. And so likewise, we were kept in servitude to the basic fundamental guardrails and practices of the Laws of Moses that were appropriate for spiritually immature children.” (Gal 4:1-3, GCTM)

2. Does the translation want to be a word-for-word translation (best for brevity and marketability), or does it also want use more words to convey the broader context to include necessary background, cultural bridges, emotional passion, and the implied life application aspects of the original text (best for really understanding what the original Koine Greek listeners were hearing)?

For example, consider Galatians 5:12:

The ESV translates Galatians 5:12 as:

“I wish those who unsettle you would emasculate themselves!” (Gal 5:12, ESV)

This is an accurate word-for-word translation of the original Greek text. So, why is this a problem? It is a problem because the average American reader when reading this will think that Paul is being sarcastic, or suggesting violent retribution, or some other harsh or cynical interpretation. But a first century Jew living in that Greek culture, especially one who knows Paul personally, would not think that at all.

There is some critical context that would be known to the first century Jewish reader that is necessary to keep in mind in order to properly understand what Paul is intending to communicate. Those who were raised Jewish (which would likely be true of those advocating adhering to the Mosaic covenant) would have memorized Deuteronomy 23:1 (along with the rest of Deuteronomy) in their schooling before they were 12 years old. Here is that verse in the ESV:

“No one whose testicles are crushed or whose male organ is cut off shall enter the assembly of the LORD.” (Deut 23:1, ESV)

In order to convey Paul’s full intended meaning, an explanatory translation should fill in the gaps caused by this cultural ignorance so it can communicate what the first century Jewish Christian was actually hearing when he heard these words. Here is how the GCTM explanatory translation translates and explains this verse:

“For those who insist on the necessity of circumcision, here is a constructive suggestion that might end up saving their souls: instead of just cutting off their foreskins, let them cut off all their genitals and then the exclusion of Deuteronomy 23:1 would apply to them and they would clearly see that it is the Mosaic Law that bars their entry into the kingdom of God. Perhaps then they would see they have to abandon their hope in the Laws of Moses and take refuge only in the cross of Christ.” (Gal 5:12, GCTM)

Paul’s hope here is that with this illustration, those errant voices would clearly see the road they begin to travel down (by advocating circumcision) ends up in a very bad place for their souls, and they should abandon traveling on that road in favor of seeking refuge, salvation, and sanctification ONLY in the cross of Christ. An explanatory translation can convey all that, whereas a word-for-word translation cannot.

3. Does the translation want to restrict the translated context to the particular verse being translated (even though with this approach it is easier for the reader to take the translated verse out of context), or does it want to include the contextual meaning that may have been specified several verses earlier (this requires longer translations, but less likely to have verses be misunderstood because the context has not been lost).

For example, In Galatians 3:20, the ESV says:

“Now an intermediary implies more than one, but God is one.” (ESV)

Although this verse actually translates this word for word from the Koine Greek, when this verse is read all by itself it is almost non-sensical, and subject to all sorts of misconstruing if someone wants to do so by taking it out of context. A careful study of the foregoing and following verses provides the context which when inserted into the translation of verse 20 helps to clarify the meaning. So, for example, in the GCTM translation, this appears as:

“But (before Jesus came) our relationship through Moses the mediator was not the same as when Abraham interacted directly with God.” (Gal 3:20, GCTM)

The Message also provides external text in the translation of this verse:

“But if there is a middleman as there was at Sinai, then the people are not dealing directly with God, are they? But the original promise is the direct blessing of God, received by faith.” (Gal 3:20, MSG)

J.B. Phillips puts verses 19 and 20 together into a single unit in order to provide the necessary context:

“Where then lies the point of the Law? It was an addition made to underline the existence and extent of sin until the arrival of the “seed” to whom the promise referred. The Law was inaugurated in the presence of angels and by the hand of a human intermediary. The very fact that there was an intermediary is enough to show that this was not the fulfilling of the promise. For the promise of God needs neither angelic witness nor human intermediary but depends on him alone.” (Gal 3:19-20, PHILLIPS)

4. What will be the policy on the formalism of the English in the target text? Does the target language want to be precise, formal, grammatically and syntactically correct English (e.g. ESV), or does the target language want to be in the more casual colloquial language used in everyday conversations between friends (e.g. MSG)? The first approach can make it more difficult for those not well educated in the formalism of higher English, but the latter can end up being off-putting to those who want to see the Scriptures handled with the reverence and respect of a formal translation. (Really the same thinking as the question about whether men should go to church in a suit and tie, or whether blue jeans and t-shirts are okay—or is it okay to have English sentences without either a subject or a verb, and mixed structure, like this one?)

To illustrate this aspect of the translation philosophy, we offer the following examples:

o According to the Introduction to the New Testament of The Message, its "contemporary idiom keeps the language of the Message (Bible) current and fresh and understandable". Peterson notes that in the course of the project, he realized this was exactly what he had been doing in his thirty-five years as a pastor, "always looking for an English way to make the biblical text relevant to the conditions of the people".

o In the Preface to the 1995 edition of the New American Standard, not only does it say one of the four main goals of the translation is that “These [this translation] shall be grammatically correct.” Then it goes on the explain the precise rules that were followed in translating the various Greek grammatical forms into English grammar. Fully half of the entire preface is devoted to the different rules it used in making sure the grammar of the English was as precise and correct as they could make it.

5. How should a word be translated? Options are:

a. Use the closest English word to the Greek word (but sometimes, the closest English word is not very close), or

b. Use a relevant phrase to more completely convey the original meaning (but this can lead to long wordy explanations that end up obscuring the focus of the context), or

c. Don’t translate a specific word; instead translate the intended meaning of the entire section (but this can lead to error if the translator does not properly understand the Holy Spirit’s intended meaning), or

d. Etc.

This last aspect (#5 above) is particularly problematical. For most of the really important theological concepts used in the Koine Greek scriptures, there is no single word in the English language that properly represents the meaning of the original Greek word. The problem is either one of scope, or sometimes even of adequately accurate definition. So, a translation that uses the translation philosophy of translating the source Greek word into the closest English target word is often going to fall far short in representing the full meaning of the original Koine Greek text.

To see this problem in its proper magnitude, we could look at a 100 important theological concepts/words in the Greek and examine the inadequacies of translating each of them into a single English word. But for the purpose of briefly illustrating the problem, let’s just look at a few important words.

Αγαπη (agape’)—This word (and all its verbal and noun forms) is almost always translated into English as “love.” Technically and literally it means “to prefer.” In the context of most (if not all) of its uses in the New Testament, it means “prefer the benefit of the other over (at the expense of) your own benefit.” The quintessential example of this is God preferring our benefit over His own even when it means having to do so at such great expense that it requires the sacrifice of His own Son to secure our benefit. When the scriptures enjoin us to agape’ each other, it means what Paul says in Philippians 2:3 when he says we should act toward each other in such a way that is characterized by:

§ “count others more significant than yourselves” (ESV)

§ “value others above yourselves” (NIV)

§ “let each esteem others better than himself” (NKJV)

§ “consider others as more important than yourselves” (CSB)

§ “Put yourself aside, and help others get ahead.” (MSG)

§ “regard one another as more important than yourselves” (NAS)

§ “thinking of others as better than yourselves” (NLT)

So, does this “technicality” make a significant difference in the way a passage is understood? Well, consider the following few examples of what is prolific throughout the New Testament:

1 John 2:10:

“1The Christian who is sacrificially loving and caring for their brother or sister in Christ—that Christian dwells in the light, and is not likely to be tripped up by the darkness.” (GCTM)

Vs.

“Whoever loves his brother abides in the light, and in him there is no cause for stumbling.” (ESV)

1 John 3:1:

“Open your eyes! You’ve got to realize what kind of love the Father has given to us for each other—a love that is self-sacrificing and devotedly caring for each other. And because we have this kind of love for each other we will be known as children of God, because that’s what we really are! And because of this kind of love, the non-Christian people of the world will not really understand us because they never really understood Jesus (who was the embodiment of this kind of love for us--a self-sacrificing and devotedly caring love).” (GCTM)

Vs.

“See what kind of love the Father has given to us, that we should be called children of God; and so we are. The reason why the world does not know us is that it did not know him.” (ESV)

1 John 3:11:

“For this is what God has always been proclaiming by His word and His deeds, that we should be self-sacrificing and devotedly caring for one another.” (GCTM)

Vs.

“For this is the message that you have heard from the beginning, that we should love one another.” (ESV)

1 John 4:7:

“Beloved, you all should be self-sacrificing and devotedly caring for one another because that’s the kind of love that comes out of the very nature of who God is. And everyone who is committed to the benefit of the other person no matter what the cost to themselves, that person is born of God and really knows God.” (GCTM)

Vs.

“Beloved, let us love one another, for love is from God, and whoever loves has been born of God and knows God.” (ESV)

1 John 4:19:

“How can we reasonably expect ourselves to sacrificially love and devotedly care for others? Because this is exactly how God has always loved us.” (GCTM)

Vs.

“We love because he first loved us.” (ESV)

1 John 4:20-21:

“If you claim to actually prefer God over yourself, but there is still at least one Christian brother or sister who you still do not prefer more than yourself, then you are kidding yourself. For if you do not have a self-sacrificing preference for your Christian brother or sister who you can actually see, then you certainly can’t really prefer God whom you have not seen. 21And so we have this charge from Him, that the one who truly loves God should also sacrificially and devotedly care for their Christian brother and sister.” (GCTM)

Vs.

“If anyone says, "I love God," and hates his brother, he is a liar; for he who does not love his brother whom he has seen cannot love God whom he has not seen.

21 And this commandment we have from him: whoever loves God must also love his brother.” (ESV)

We could show hundreds of places throughout the New Testament where translating the word “Αγαπη” (agape’) into the English word “love” significantly impoverishes the meaning of the passage and is likely to leave the reader with a wrong understanding of what God is intending to communicate to them. But if one is constrained to pick the closest single English word to correspond to the Greek word Αγαπη(agape’), then the English word “love” would probably be as close as you can get (athough it is not adequately close to properly convey the meaning of the Greek text).

Δικαιοσυνη (dikaiosune’)—This word is almost always translated into English as “righteousness.” That would be fine if the average American reader had the same definition in their head as the Apostles had when they wrote the original text. But if you ask the average American reader to define the word “righteousness,” you will get definitions like “doing good things” or “doing the good things God says are good things” or simply “Godly acts.” But those definitions are not even close to the definition that this word has in the original; but more to the point, those definitions tend to convey the exact opposite intent of that word. Listen to what Paul says in Galatians 2:21 about this word:

ει γαρ δια νομου δικαιοσθνη, αρα Χπριστος δωρεαν απεθανεν

Translation: For if righteousness (for us) could be achieved through adherence to the Law (of Moses), then Christ died for no reason.

In other words, righteousness (for us) has nothing to do with our good works, even if those good works conform to the Ten Commandments or to any of the rest of Laws given by God through Moses to us at Mt. Sinai.

So the word “dikaiosune’” obviously cannot mean “our good works” even when those good works align with the Laws of God given through Moses.

That then begs the question: So, what exactly is the New Testament definition of the word “dikaiosune’”? It is defined by various Greek scholars as:

“Judicial approval (the verdict of approval); in the NT, the approval of God (divine approval). Refers to what is deemed right by the Lord (after His examination), i.e. what is approved in His eyes.” [BibleHub.com, HELPS]

“The state of him who is as such as he ought to be” and “the state acceptable to God which becomes a sinner's possession through that faith by which he embraces the grace of God offered him in the expiatory death of Jesus Christ” [Thayer]

“Christian justification” [Strong]

So, in New Testament usage, especially by Paul in the book of Galatians (but also by other apostles in other NT writings), “righteousness” is something given to a Christian by God because of the sacrifice of Christ; and it has nothing to do with any good or bad works that Christian does or does not do. Some may think it is not fair that someone who has done terrible things could be declared “completely righteous” (and by inference: “not guilty of anything”) by God, but that opposing assessment doesn’t matter, because God’s opinion is the only one that counts. (And the sacrifice of Christ is that powerful—or as theologians would say, “It is that efficacious!”)

Compare these verses to see the likely detrimental consequences of translating the Greek word dikaiosune’ as the English word righteousness:

“If you know that he [God] is righteous, you may be sure that everyone who practices righteousness has been born of him.” (1 John 2:29, ESV)

Vs.

“If you know what being approved by God looks like, you will also know that everyone living in that approval from God is one of His children.” (1 John 2:29, GCTM)

Notice, in the case of the ESV translation of 1 John 2:29, the average reader is likely to get in the impression that this verse is saying that everyone who practices (continually) doing good things is in God’s family. That reader will likely be worried about their status before God when they do not practice doing good things. This misunderstanding severely undermines the Gospel message and takes the focus off the finished work of Christ and puts it on the unfinished work of the Christian. This is an abominable perversion of the Gospel.

On the other hand, the GCTM translation conveys the idea that if a person understands that their righteous standing in God’s sight is given to them because of the finished work of Christ and it does NOT depend at all on the things they do, and a true Christian rests in the peace of that knowledge, then that person is indeed a member of God’s family. Here the focus is on the power of the cross, and not on the actions of the Christian.

Do you notice that these two translations can produce the exact opposite understanding in the mind and heart of the average Christian, and this error is because the translator simply chose to translate the word dikaiosune’ as the single word righteousness in the translation.

There are many other very important words that too often just use the gloss (flash card showing closest English word) vocabulary. It can be demonstrated with passage after passage from hundreds of places throughout the New Testament why that gloss word is either inadequate or misleading as the word that accurately represents the meaning of the source Greek word. As we have illustrated, often these errant renderings end up robbing Christ of His true glory and misleading Christians from understanding the peace and joy and grace and riches of Christ and his genuine agape’ love for us and our motivation to extend that love to other children of God. It is the intention of an explanatory translation to correct these oversights.

For the student who wishes to study these further, we can recommend doing deep and thorough word studies of the following words, paying close attention to their original literal meaning. And then using that better understanding of the Greek word, translate those passages that contain that word and watch the Scriptures come alive and become powerful in wonderous new ways. Here are some words to start with:

Λογος (logos)—yes, this word is often translated “word” but its meaning is much broader than that and some Greek scholars would prefer to translate it as “logic.” Christ is called the logos of God. How would it change the meaning and implications of those passages if you asked yourself in what ways is Christ the logic of God?

Χαρις (karis or charis)—this word (and all its other forms) is usually translated as grace or joy. But its original meaning comes from the Greek word χαρ which means to lean. But this must be understood in the cultural context of ancient tribal leadership where the leader showed his strong favor toward a special person by leaning toward him (this leaning was considered a detraction or degradation of the stature or voluntary humiliation of that leader in which he willingly sacrificed to share his stature with the one to whom he was leaning). It is a perfect picture of God giving his grace to us, and when He does that, we experience great joy in being the recipient of that extreme recognition and favor. Ponder what a difference the passages about grace and the joy of the Lord might convey if this metaphor was more completely represented in the translation.

Ηρηνη (eire’ne’)—this word is usually translated “peace,” but it really is the same word as the Hebrew word shalom which means wholeness of your soul. When Jesus promises us His peace, what if He was really saying, “I give you the same wholeness of soul that I have”?

Ονομα (onoma)—This word is almost always translated as “name.” But the concept of onoma in the first century Greek (and Roman and Hebrew) world was something much more than only a moniker to use when referring to a person. It means all these things together: moniker, public status and stature, responsible social obligation, authority, reputation, legal standing, and more. How might it change your understanding if you considered the full meaning of this word when interpreting verse about doing something “for my name’s sake,” or taking the name of God in vain, or “he has not believed in my name,” or “the works that I do in the name of my Father,” etc. A similar concept is what it means to be a son/child of the King. As such, you take on the responsibility to uphold your Father’s reputation, His obligations, to take on his stature, and know that His reputation requires Him to pay your debts, etc.

There are many other important words that really need to be explained to include the context of the broader passage. When you do that, all sorts of fascinating, awesome, and very encouraging insights emerge. That is one of the purposes and advantages of an explanatory translation.

We do not intend to disparage closest word-for-word translations. We use many examples in this article from the ESV. The reason for that is that the author often uses, and uses with confidence, the ESV translation. But it is important to realize the translation philosophy used by translations such as the ESV has limits, and sometimes those limits are so limited that they are disturbing and discouraging. But on the other hand, the potential weaknesses of an explanatory translation (such as the GCTM or MSG or PHILLIPS or others) is that it relies heavily on the translators’ understanding of the Holy Spirit’s primary intent in a passage. And given that God never does anything for only one apparent reason, the translators will no doubt end up obscuring those intents that are not apparent to them. So, ultimately, we recommend that if you are not an expert Greek scholar, you would be best served to use multiple translations side by side when you are studying a passage while expecting the Holy Spirit to show you what He wants you to see at that time in your life’s journey.

In case you are wondering, this author (the primary and supervising author of the GCTM version) often uses not only the Koine Greek source documents (BibleHub.com’s Nestle 1904+) when studying the New Testament, but also frequently refers to the ESV, MSG, YLT98, KJV, AMP, and sometimes CJB, BSB, NAS, NIV, PHILLIPS, and NLT. All of those were consulted frequently, when finding the best words for translating the Koine Greek seemed potentially tricky.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our goal is to produce a translation from the original Koine Greek manuscripts that is true to the original Koine Greek but is focused more on communicating to a 21st century American audience what the first century Greek speaking audience was experiencing and feeling as they read and thought about the apostles’ writings. Our translation philosophy has five directing guidelines:

1. Brevity is not a constraint. When necessary, as it often is, we will use as many words as necessary to convey the fuller meaning of the source text. Because we will end up doing a lot of explaining, this will sometimes mean that the number of words will be much greater than what appears in the Greek source manuscript.

2. Word-for-word translation is not better than using whatever words are necessary to convey as much of the full meaning and emotion of the source text.

3. When necessary, the translation of a verse will need to remind the reader of the overall context that the different parts of that verse is referring to. This will necessitate inserting phrases into the verse that are not in that particular verse in the original source, but are implied in the overall context and appear explicitly in other verses in the source manuscript. We do this because often verses are studied and memorized in isolation from the overall context, so by doing this, we hope to reduce the tendency of some Biblical students to take verses out of context (or misunderstand them entirely).

4. Although grammar is helpful in reducing ambiguity, we will not always use the formalisms of classical English when the use of colloquial phrasing will help the text seem more personal (and come alive) to the average American reader.

5. We prefer to explain the full meaning of the original Greek words the way they would likely be understood by an educated native Greek speaker in the first century. This is in lieu of attempting to use the closest single English word when that word would be misleading or even just limited in its comprehension of the original Greek word.